These laws prevented Black children’s education in Westerville.

In 1829, the state legislature passed a law forbidding Black students from attending schools that were supported by tax dollars. The laws continued to evolve throughout the 1840s and 1850s, eventually allowing for the creation of separate Black schools if there were at least 30 Black children in a school district. Districts with fewer Black students were not required to allow Black students to attend.

Westerville’s willingness to accept Black schoolchildren was put to the test. In fall 1857, the Thomas family moved to the almost exclusively white town to send their 12-year-old son Samuel to Otterbein. Samuel was described as an intelligent, hard-working boy, and he “spoke and prayed with great fervency, so much so that he was accredited with gifts and graces that seemed to set him apart for the ministry.” Possibly because of his young age, Samuel did not apply to Otterbein right away. Instead, he and his older brother William attended the local village school. The following winter, William returned to the village school. We do not know if Samuel or any of their other siblings attended during the 1858-1859 winter term.

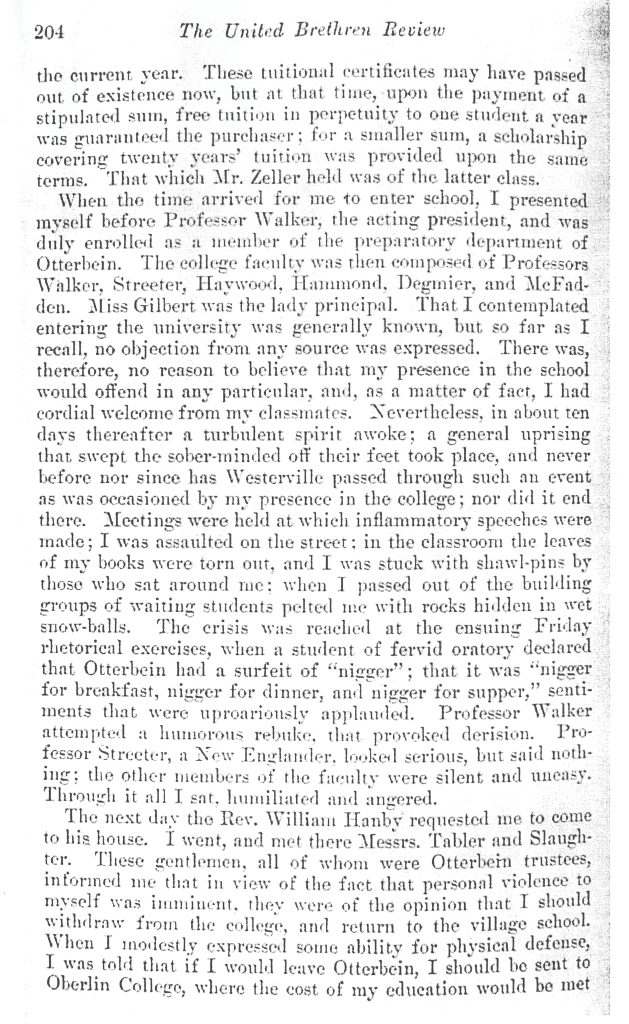

In November 1859, Samuel applied for admission at Otterbein. The trustees rejected his application because he was too young. Within days, 16-year-old William applied for admission. They debated his application for days but eventually accepted him. A group of white students soon began to verbally and physically harass William. During a meeting at Otterbein trustee William Hanby’s house, the trustees threatened to expel him. William Thomas said, “I was told that my presence imperiled the very existence of the school.”

Two of William’s younger brothers were still at the village school. He recalled, “Such was the racial prejudice aroused by my presence in Otterbein, that one of the school trustees, a Mr. Clymer, directed the teacher in charge to forbid their further attendance.” The teacher, Hezekiah Pennell, acquiesced and sent the boys home. The next day, their parents sent them right back. According to William, “When Mr. Clymer found it out, he came in person to the school and forcibly ejected them from the building, adding threats of severe punishment if they attempted to come back, at the same time ordering Mr. Pennell to keep the door locked to prevent their reentrance.” The law was technically on Clymer’s side, as they were the only two Black students in the district. Their mother, Rebecca, contacted Governor Salmon P. Chase, one of the leading politicians in the country dedicated to racial reform. Chase stepped in, and the Thomas brothers returned to the village school. Samuel was never admitted to Otterbein, and William did not return for another term. The Thomas family left Westerville in 1860. Although light-skinned, William struggled with the implications of his skin color for the remainder of his life, and his frustrations culminated in a book he authored proclaiming his belief in the inferiority of African Americans to white Americans.[1]

Definitions

A preconceived, usually negative attitude towards a person because of some aspect of their identity, including but not limited to racial or ethnic background.

Definition adapted from the American Psychological Association

References

[1] William Hannibal Thomas, “Memories of Otterbein Half A Century Ago” (T11017), File on Thomas, William Hannibal (T11), ca. 1910, Westerville History Museum; John David Smith, Black Judas: William Hannibal Thomas and the American Negro (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2019), Ch. 1; Ancestry.com. 1860 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009.

How to Cite This Source

Please cite this toolkit (Chicago Manual of Style) as 'Westerville History Museum, "Racism in Westerville History," Westerville Public Library, last modified January 23, 2023, https://westervillelibrary.org/racism-history.

Need a citation in a different style (such as MLA or APA)? Try this citation generator.