People who lived in Westerville took part in the struggle for emancipation.

The Underground Railroad has left a strong imprint in Westerville’s collective memory. This is largely due to the fame of the song “Darling Nellie Gray,” written by Benjamin Hanby, a member of an abolitionist family. However, the dangers associated with Underground Railroad activity meant the names of the people who sought freedom were not written down, nor did they survive in the oral traditions of Westerville’s white families. We only know the name of one freedom seeker who came through Westerville. Thomas Harrison fled from a plantation in Lexington, Kentucky after he learned that two of his brothers had been sold. He traveled at night and crossed the Ohio River on a makeshift wooden raft. In Westerville, he hid in the basement of the Stoner House, an inn and tavern along State Street, before continuing to Canada.[1]

The struggle for emancipation took many other forms. One group of people enslaved in North Carolina, the Alstons, gained their freedom through their owner’s will before settling in East Orange near the present-day Alum Creek Lake & dam. A white pro-slavery neighbor, Leo Hurlburt, sneered at their presence and began calling the area “Africa.” The name stuck.[2]

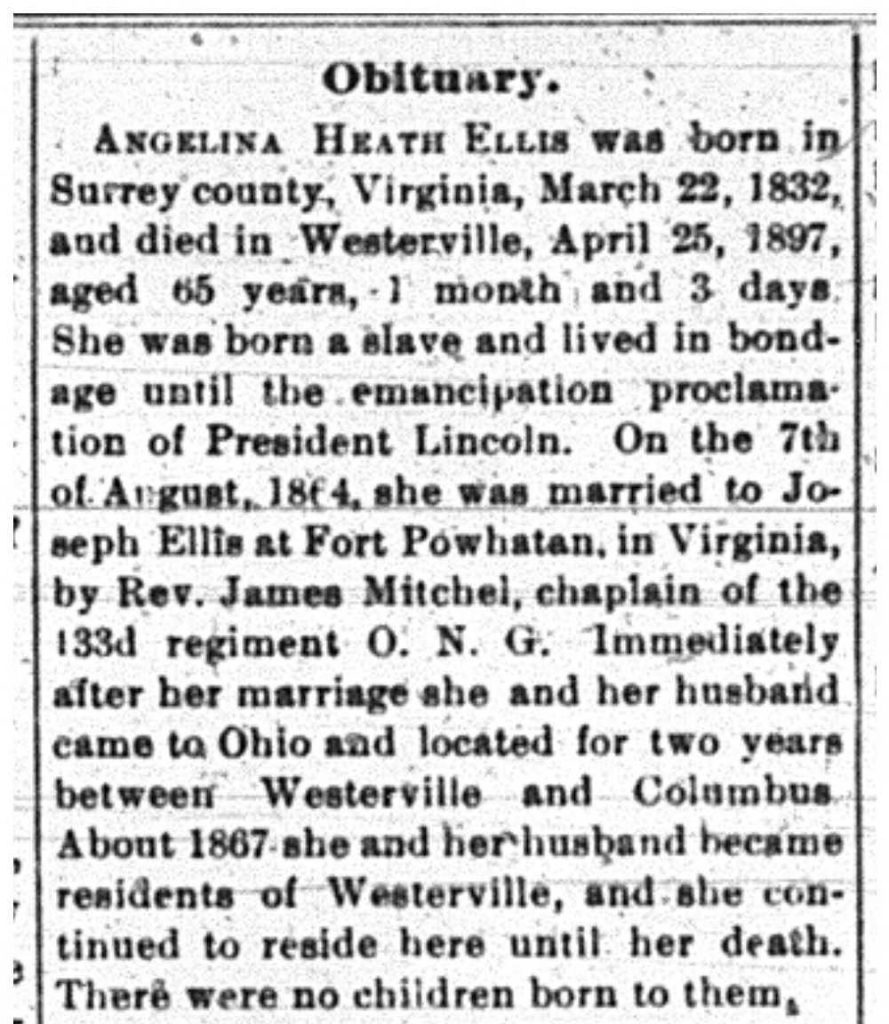

Others self-emancipated by making their way to the safety of Union lines during the Civil War in the wake of the Emancipation Proclamation. Angelina Heath was born enslaved in Surry County, Virginia in 1832. Heath and a man named Joseph Ellis, along with large numbers of other Black refugees, made their way through the war-torn landscape to nearby Fort Powhatan. An army chaplain married Heath, Ellis, and about 19 other couples who arrived safely at Fort Powhatan, a momentous occasion since most enslaved people – who the law treated as property rather than as people who could enter into legal contracts – had not been allowed to legally wed. The Ellises and some other newlyweds soon made their way to Franklin County, Ohio.[3]

Definitions

Someone who supports a movement to end something, especially slavery.

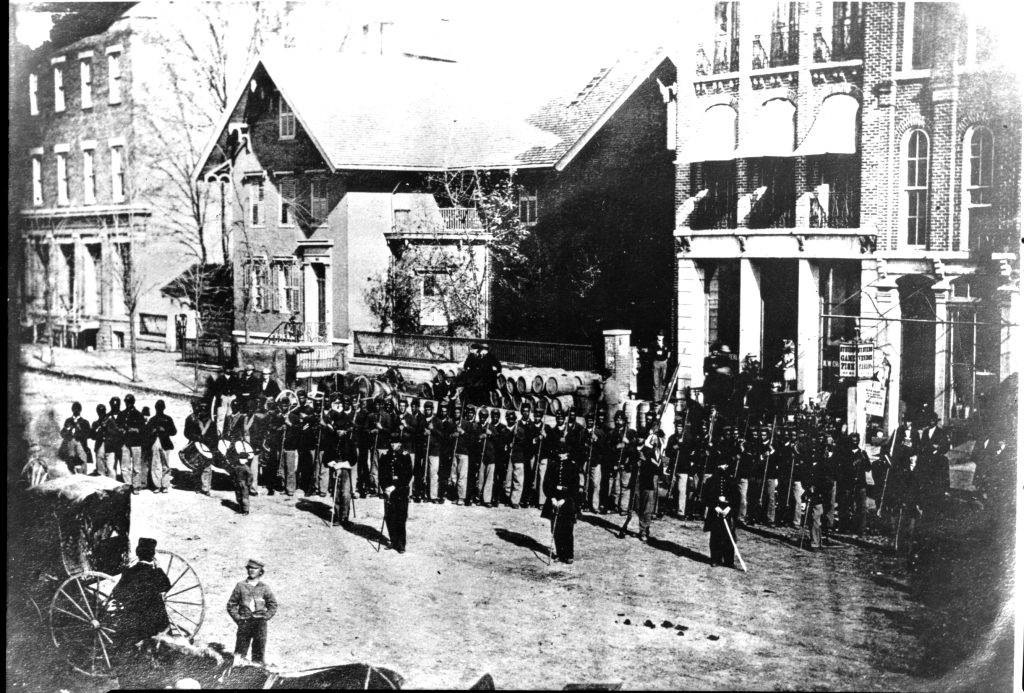

Some men, like William Perry Milton, worked towards emancipation on a grander scale, as part of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). These soldiers could have decided to fight in the Civil War for a variety of reasons, whether it was to fight slavery, out of a sense of duty or patriotism, for money, to prove their manhood, to be recognized as equals to whites, or to have an adventure. But regardless of their individual motivations for enlisting, men like Milton fought for a government that was working to end slavery.

References

[1] Hugh Fullerton, “De Lawd of Green Pastures, Son of Two Escaped Slaves, Is Hero of Amazing History,” Ohio Memory, Wilbur H. Siebert Collection, Ohio History Connection, accessed 10/6/2022, https://www.ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/siebert/id/4072/rec/12.

[2] James R. Lytle, 20th Century History of Delaware County, Ohio and Representative Citizens (Chicago: Biographical Pub. Co., 1908), 474; Alston Family Vertical File (A15), Westerville History Museum.

[3] Public Opinion, 4/29/1897.

How to Cite This Source

Please cite this toolkit (Chicago Manual of Style) as 'Westerville History Museum, "Racism in Westerville History," Westerville Public Library, last modified January 23, 2023, https://westervillelibrary.org/racism-history.

Need a citation in a different style (such as MLA or APA)? Try this citation generator.