With all this evidence that racism has been a major problem in Westerville over the past 200 years, why have these stories not been told before now? A letter written in 1958 serves as the lynchpin for understanding Westerville’s deliberate attempts to collectively forget its Black history.

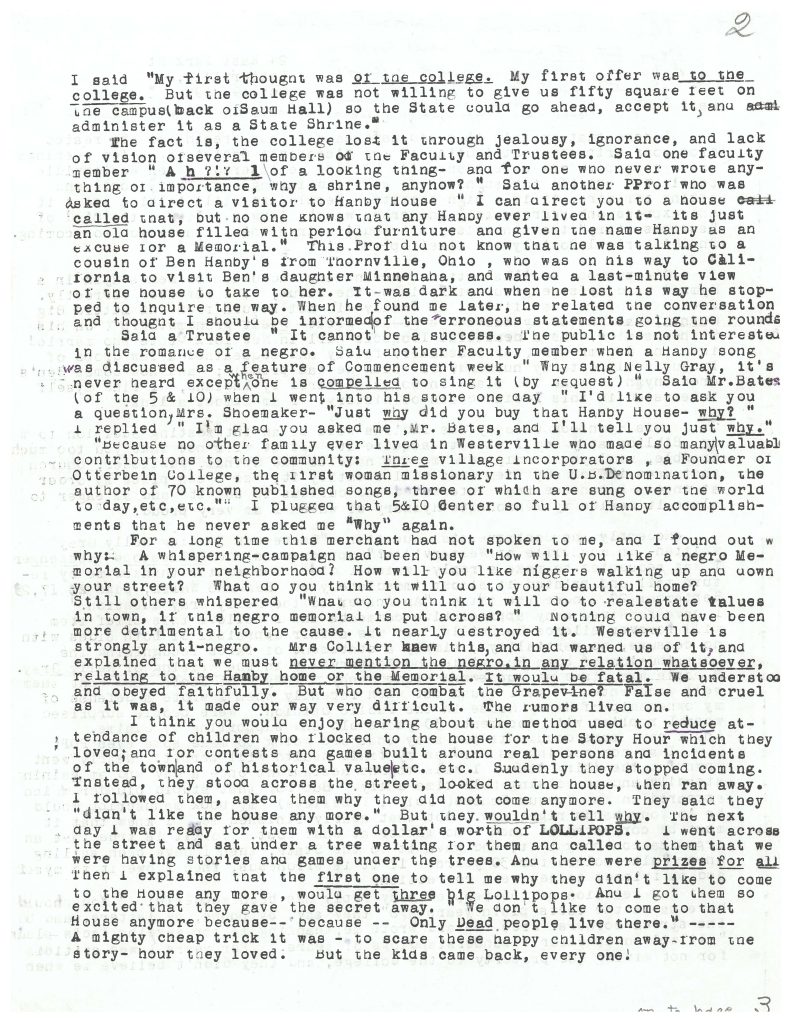

Dacia Custer Shoemaker was a white woman who spearheaded the effort to save the Hanby House, the home of an underappreciated white composer from an abolitionist family, in the 1930s. A vocal contingent of white Westerville residents scorned the fact that one of his most successful compositions was an anti-slavery song. According to Shoemaker, an Otterbein trustee said of the house, “It cannot be a success. The public is not interested in the romance of a negro.”

White people were also concerned about what the preservation of the Hanby House would do to Westerville’s reputation. Shoemaker described a “whispering-campaign” throughout town. People made spiteful comments like, “How will you like a negro Memorial in your neighborhood? How will you like niggers walking up and down your street? What do you think it will do to your beautiful home? … What do you think it will do to realestate [sic] values in town, if this negro memorial is put across?”[1]

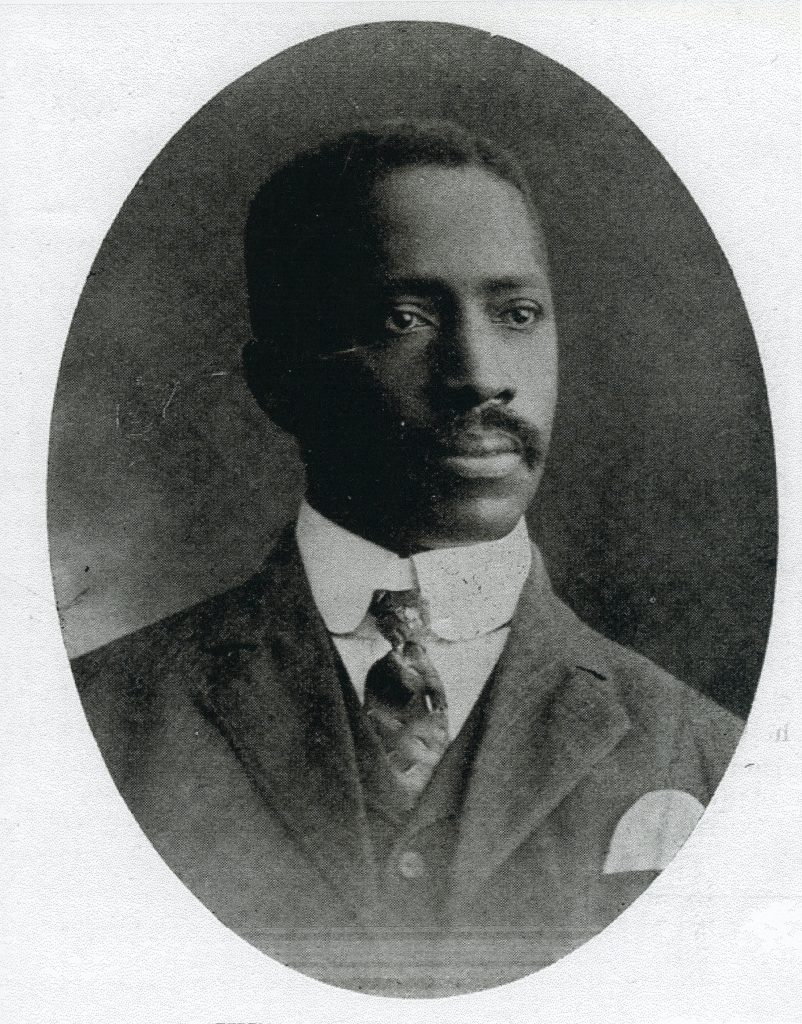

Shoemaker’s critics would have known that Black families had lived in the house even longer than the Hanby family had. A formerly enslaved man, Squire Fouse, had purchased the house over four decades earlier. His son, William Fouse, lived there while studying at Otterbein, becoming its first Black graduate in 1893. After Squire’s death in 1909, William’s stepmother Martha ran it as a boardinghouse for other Black families and eventually sold the building to EWB Curry, who ran a school for African Americans in Urbana, Ohio.[2] Eventually the house came under white ownership again, but the memory of its African-American inhabitants and their strong connections with Black education would have remained.

William Fouse helped raise money for the house’s preservation and described a meeting with Shoemaker in 1937. They discussed “what would be most appropriate to have as one feature” in the house. John R. King, who worked at Otterbein, made a suggestion, but Shoemaker was “non-commital.” Fouse was afraid that Shoemaker was acting out of “timidity and fear.” King’s suggestion seems to have had something to do with slavery or Black history because Fouse continued, “I would not wave the bloody shirt nor open wounds that are healing. I would not fail however, to allow the scar to be seen that might be a warning against making similar mistakes. The ‘South’ makes not apology in all her exhibitions of past glory carrying with it in words as well as works her belief in the doctrine of – some men up but other men down… The entire subject is too personal for me to say anything more.”[3]

As Shoemaker saw it, she and her allies had a choice to make: talk about the home’s connections to Black history and potentially doom it to failure, or focus on Benjamin Hanby’s musical talents and have a chance at saving it. In her 1958 letter, Shoemaker continued, “Westerville is strongly anti-negro. Mrs Collier [Ben Hanby’s sister] knew this, and had warned us of it, and explained that we must never mention the negro, in any relation whatsoever, relating to the Hanby home or the Memorial. It would be fatal. We understoo[d] and obeyed faithfully.”[4]

The consequences of this missed opportunity have reverberated for decades and had devastating effects on Westerville’s memory of its Black residents. Only interpreting Westerville’s Underground Railroad history in a relatively shallow manner was a deliberate choice – one that allowed people to avoid deep, comprehensive, meaningful engagement with Westerville’s complicated past. It was the easy way out - after all, if Westerville helped enslaved people achieve freedom, it couldn’t possibly be a racist place – could it? This became the predominant narrative in Westerville and has been perpetuated by the museum. However, it is oversimplified and has never represented a holistic interpretation of BIPOC experiences in Westerville. People of color – particularly students – continue to face discrimination.

But there are reasons to hope. Westerville is hungry for new perspectives and more historically accurate narratives, especially as its demographics become more diverse (as of the 2022-2023 school year, Westerville students are almost 50% non-white and represent 64 different countries).

Many people in Westerville are working hard to transform it into an anti-racist community:

- Otterbein students and Westerville City School students and teachers led Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in 2020, highlighting the injustice and violence that Black Americans across the country continue to face from the police.

- Community members banded together to create WeRISE for Greater Westerville, a nonprofit dedicated to anti-racism.

- Leadership Westerville gives awards to honor students and community members who exemplify the characteristics of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

- The Westerville Education Foundation and other community organizations have partnered together to place more diverse books in classrooms so students can see themselves represented and better empathize with each other.

- Otterbein has been designated as a Truth, Racial Healing, and Transformation Campus Center.

- The Westerville History Museum has an ongoing partnership with OSU and the Kirwan Institute to explore racial covenants in Westerville neighborhoods.

These are just a few of the many ways (as of 2022) that people who live and work in Westerville are building it into a better, more equitable place. The work is not yet finished but being honest about Westerville’s past will serve as a strong foundation for an anti-racist future.

Definitions

Black, Indigenous, and People of Color.

References

[1] Letter from Dacia Shoemaker to Earl Hoover (H145689), Westerville Historical Society Hanby Collection (H145), 1956 or 1958, Westerville History Museum.

[2] Freeman newspaper, 3/27/1909; 1913 Westerville Directory (D10022), File on Directories (D10), Westerville History Museum.

[3] Letter from William H. Fouse to J.R. King (H52054), File on Historical Society and Hanby House (H52), 7/6/1937, Westerville History Museum.

[4] Letter from Dacia Shoemaker to Earl Hoover (H145689), Westerville Historical Society Hanby Collection (H145), 1956 or 1958, Westerville History Museum.