Migration laws made it difficult for Black settlers to move to Westerville.

Christopher Hendrick Swears and his family were some of Blendon Township’s earliest Black settlers in the 1820s. They tried to carve out a life for themselves somewhere near Blendon Corners, the present-day intersection of Routes 3 and 161.[1]

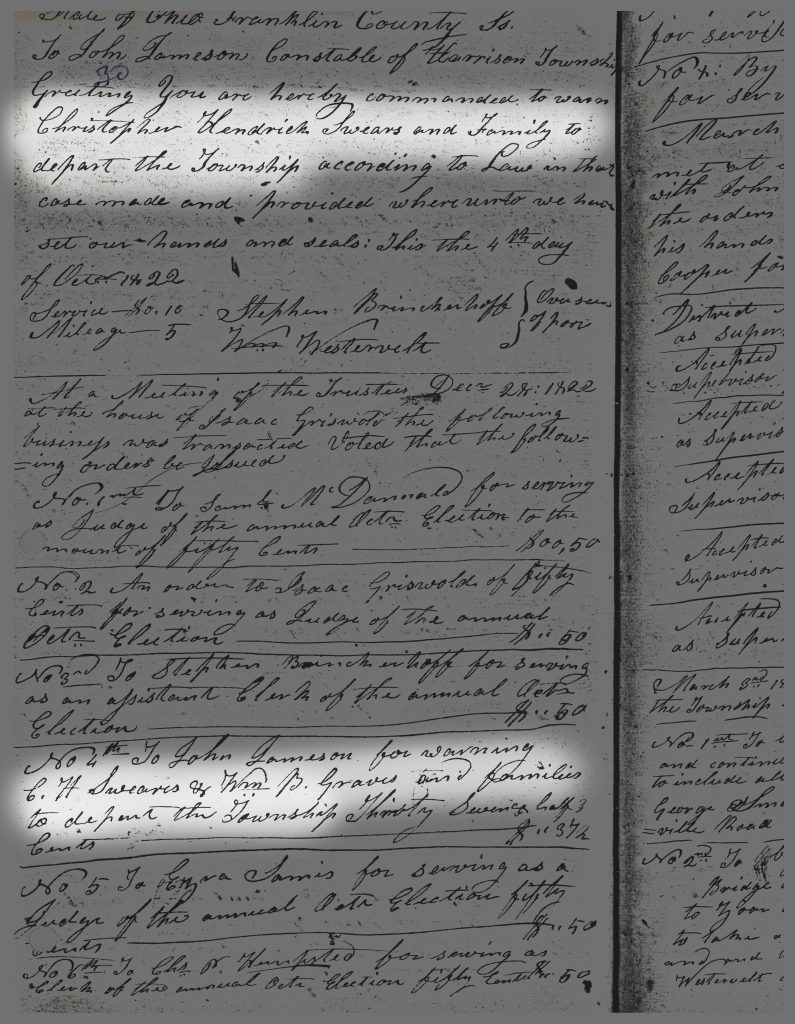

In October 1822, in accordance with Ohio poor law, township representatives ordered Swears to depart the township.[2] The township had Overseers of the Poor, who were in charge of caring for the township’s impoverished, but that privilege only applied to people who had attained legal settlement by residing in the township for a year. People who had not yet attained legal settlement and might become a public charge could be ordered to leave.

Definitions

Laws intended to reduce poverty, but only people who met certain qualifications were eligible for assistance; an early form of welfare.

If Swears lived in the township for less than a year and was new to the state, he already faced an incredible financial burden. He would’ve been required to produce proof of his family’s freedom, register with the country clerk (which cost 12.5¢), and put up a $500 bond (equivalent to $12,684 in 2022). It is likely the Swears couldn’t afford to register or put up bond at all, and that’s why the trustees told them to go.

It must have been devastating to be expelled from the township – it was right around the time of his daughter Luvinia’s birth, with the cold of winter fast approaching. Swears may have tried to fight or ignore the order, because the township trustees voted again just after Christmas to order Swears out. But despite these systemic barriers to settlement, the Swears family were determined to make Blendon Corners their long-term home. Christopher Swears appeared in township records again in August 1826 when the township was divided up into school districts.[3] They stayed in the area at least through 1830.[4]

Definitions

An obligation to pay a certain amount of money as an assurance of something – in this case, paying a fee to demonstrate that they could support themselves financially.

References

[1] Based on the 1830 Federal Census, one of Swears’ neighbors was Francis Olmstead. An 1830 map shows that Olmstead owned land south of Blendon Corners. Swears presumably lived somewhere in this vicinity too. Ancestry.com, 1830 United States Federal Census [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010; “Map of U.S. Military Lands in Franklin County Ohio in 1830” (M02099), File on Maps: Westerville and Blendon Township, Franklin County (M02), 1830, Westerville History Museum.

[2] Harold Hancock, ed., “Minutes of the Trustees of Harrison and Blendon Township” (G29088), File on Government : Blendon Township (G29), 1987, Westerville History Museum, page 16.

[3] Ibid., 16, 28.

[4] 1830 United States Federal Census.

How to Cite This Source

Please cite this toolkit (Chicago Manual of Style) as 'Westerville History Museum, "Racism in Westerville History," Westerville Public Library, last modified January 23, 2023, https://westervillelibrary.org/racism-history.

Need a citation in a different style (such as MLA or APA)? Try this citation generator.